In the fall of 1983, I boarded the Trans-Siberian Railroad in Europe and slowly made my way back to Beijing. Someone I met on the train remarked: ‘Your timing’s really good, because if you had come back just a little earlier, you would have encountered the last sparks of the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign. As a recent returnee from Europe, you certainly would have made quite a target, wouldn’t you?’ Having experienced the turbulence of the Cultural Revolution, I couldn’t help but feel somewhat anxious at the news that yet another campaign had been launched.

It was September 1981 when I left China. At the end of the Cultural Revolution, China’s isolation and backwardness were painfully evident. As part of the open-door policy, the leadership decided to send a selected group of scholars and educators overseas for advanced training. At the time I was teaching at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art). After sitting for a national exam, I was one of the lucky few to be chosen for this rare opportunity. As one of the first artists from China’s art academies to be sent overseas through official channels, I was assigned to a two-year program of study at the University of Minnesota in the United States. Towards the end of my stay, I travelled to Europe where I visited 12 countries in three weeks and took many thousands of slides and photographs. I clearly recall a visit I made to the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, which houses the world’s largest collection of paintings by Gustav Klimt. I had just taken out my camera when a security guard stopped me. I asked if I could talk to the museum director, and when I explained to her that the photographs I took would give untold numbers of Chinese students the opportunity to see original Western masterpieces for the first time, she was very moved.

I carried the materials I had gathered first hand, together with a head full of impressions, back with me to Hangzhou. At this time the situation inside China was relatively more relaxed. Young people were eager for knowledge from the outside world, and a number of universities and institutes invited me to lecture. In the early 1980s the media was still heavily restricted in China, and it was rare to meet anyone who had been abroad; thus my first-hand knowledge, observations and experiences were enthusiastically welcomed by the audience. The Central Academy of Fine Arts put up a gigantic red poster announcing ‘Zheng Shengtian to Discuss Western Art’ in hand-brushed characters. My lectures in Beijing and Shenyang lasted for four or five hours, and hardly anyone ever left the room. In 1985 I was invited to a national oil painting conference in Jinxian, Anhui province, to present a talk on trends and developments in Western art. It was here that I first brought up the concept of postmodernism, which generated a huge amount of interest. The debut issue of the newspaper Fine Arts in China (Zhongguo meishubao) made this the subject of their lead article.i

Not long after, I was appointed as chairman of the Zhejiang Academy’s Oil Painting Department and later was made director of the Academy’s Foreign Affairs Office. Clearly, the Academy’s leadership hoped that I would maximize the usefulness of the knowledge and experience I had gained in the West. But any efforts towards academic reform were greatly hindered by obstacles encountered due to the weight of academic tradition. For example, in contrast to the situation overseas, the teaching curriculum in the Chinese art academies was highly restrictive and atrophied. It was completely unsuited to creative development. Despite our best efforts, we were able to obtain only two weeks of elective courses for students in each department. The Academy’s existing academic content was restricted to a rigidly set syllabus, and any attempt to change it was not to be lightly undertaken. Thus it was very fortunate that I was able to take advantage of my position in the Foreign Affairs Office to arrange a series of extra-curricular activities and lectures at the school. In 1984 we invited Professor Roman Verostko from the United States to conduct a seminar, illustrated with slides, on the history of Western 20th-century art—the first time this was ever done in China. Universities and academies from all over the country sent people to attend the seminar. The following year, we used the same method to invite our old friend and colleague Zhao Wuji to Hangzhou to give a studio course in oil painting. The impact of these two events on the Chinese art world proved to be both deep and far reaching.

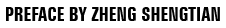

During my student days, I was often criticized for having ‘liberalist’ tendencies and for failing to abide by the rules. But I always felt that the idea of doing art without innovative thinking was ridiculous. In 1984, just after my return from Europe, Jin Yide and I were the supervisors of the graduate-level courses in the Oil Painting Department. Among our graduate students were Geng Jianyi, Liu Dahong, Wei Guangqing, Wan Lihua, Ruan Jie, Chen Ren and Wei Xiaolin. They were all very lively thinkers, and their creative work was marked by fresh ideas and innovative approaches. For example, Geng Jianyi’s painting Two People Under a Light (Denguang xia de liangge ren), depicted a poker-faced, expressionless man and woman seated rigidly in front of a table. In Chen Ren's Jump for Joy (Tupo), the action of an athlete performing the high jump against a bright blue sky was divided into three separate frames of motion. We admired how these students were able to move beyond the usual conventions of grand subjects and realist technique. At the same time, however, these same qualities made some members of the Academy’s leadership and faculty extremely nervous. As a result, an intensive three-day meeting of all department heads was held to discuss these kinds of ‘incorrect tendencies’. One speaker actually broke down in tears and denounced the students’ creativity as veering away from the path of socialism. Despite the strenuous arguments in the students’ defence put forth by myself and the other graduate-school professors, we were in the minority. In the aftermath, I wrote an article called ‘This is Not a Critique of Creativity’ (Bingfei dui quangzao de pinglun) for the campus publication New Art (Xin yishu), which criticized the politicization of art.ii As news of the controversy spread, the editors of the Beijing-based journal Art (Meishu) sent Tang Qingnian to Hangzhou to investigate the situation and conduct interviews. Not long after, the magazine published a detailed article on the development of the debate and included several images of paintings by the students.iii This became one of the most well-known and controversial incidents of the ’85 New Wave movement.

(1) People Under a Light, Geng Jianyi, 1985, oil on canvas.

(2) Jump for Joy, Chen Ren, 1985, oil on canvas, on the cover page of New Art(Xin meishu), no.4 (1985).

(3) Catalogue cover, Beyond the Open Door: Contemporary Paintings from the People’s Republic of China, 1987.

Hangzhou also developed the reputation of being one of the epicentres of the ’85 movement, as many important events took place there: the exhibitions ‘New Space ’85’, ‘Red White Black’ and ‘Last Exhibition ’86, No. 1’; the creation of groups such as the Pond Society and Red Humour International; and the establishment of the Institute Art Tapestry Varbanov, among others. Some of the most dynamic members of the contemporary art circles in other urban centres also came out of Hangzhou, including Huang Yongping, Wang Guangyi and Yan Shanchun, to name a few. Living and working there, I was keenly in touch with the pulse of the movement, and together with a number of other artists, experienced its alternating waves of excitement and despair.

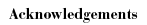

I was always on the look-out for spaces in which contemporary art could flourish. When I was offered a teaching post at San Diego State University in 1986, I took advantage of the opportunity to organize an exhibition of Chinese contemporary art at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena. Entitled ‘Beyond the Open Door: Contemporary Paintings from the People’s Republic of China’ (1987), the exhibition marked the first time that artists like Zhang Peili, Geng Jianyi, Zhang Jianjun, Xu Jiang and Wang Jianwei were seen by American audiences. In 1988, after returning to Hangzhou, I set up the Zhejiang International Institute for the Arts (Zhejiang shijie meishu yanjiuhui), which published a journal called International Institute for the Arts Bulletin dedicated to introducing overseas art movements. I also devised a plan to create a space where contemporary art could be exhibited. This actually resulted in the set-up of two different spaces in a collaborative effort between Hangzhou and Shanghai: the Hangzhou Hotel Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts Tapestry Gallery and the Art Gallery of the Shanghai Drama Institute. This marked the first attempt in China at a merger between art and the market.

The 1980s marked the birth and tumultuous growth of Chinese contemporary art. In a catalogue essay for a later exhibition I organized for the Pacific Asia Museum, I wrote: ‘After about a decade of fermentation following the Cultural Revolution, the tide of Chinese avant-garde art known as the ‘Youth Art Movement of ’85’ finally appeared. Most art critics agree that this movement was formed after China had opened its door and been exposed to Western culture. The philosophical and artistic ideas of this movement were naturally ‘shallow and confused’, but it’s attack and destructive influence on tradition and the public was so obvious as to need no explanation.'iv

A quarter of a century later, Chinese contemporary art has moved from the periphery to centre stage. Never before have Chinese artists enjoyed such positive creative conditions and environments, or such levels of international respect and recognition. Yet at the same time, they are also facing an unprecedented challenge. For contemporary artists in this new era, the critical challenge lies in whether or not they will be able to escape being completely influenced and controlled by the culture of the market and of politics. Today we are looking back at the past, reassessing the conditions of the 1980s when contemporary art was in its infancy: its passion and its idealism, its searching and its confusion, its failures and its successes. By returning to the original starting point of Chinese contemporary art, we may perhaps gain some insights and reflections that will be of benefit to our present time.

I would like to thank Asia Art Archive for inviting me to contribute original materials from that period which I have collected and preserved over many years. I hope that they will be useful for research and discussion. I would like to thank Jane DeBevoise and Claire Hsu of the Archive, who have given their most serious attention this project; and Anthony Yung, who has put great effort and meticulous care into the work, particularly in coming to Vancouver to assist me in organizing and annotating the material. To them I extend my heartfelt gratitude.

| Notes | |

| i. | Zhai Mo, ‘History, Concept, Character’ (Lishi, guannian, gexing), Fine Arts in China (Zhongguo meishubao), no. 1 (Beijing: Chinese National Academy of Arts, 1985). |

| ii. | Zheng Shengtian, ‘Not A Critique of Creativity’ (Bingfei chuangyide pinglun), New Art (Xin meishu), no.4 (Hangzhou: Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts Publishing House, 1985). |

| iii. | Xi Gang, ‘An Overview of the Main Points of the Controversy over the Creative Work of Graduate Students of the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts’ (Zhejiang meishu xueyuan biyesheng chuangzao taolun lundian zhaibian), Art (Meishu), no. 9 (Beijing: Chinese Artists Association, 1985). |

| iv. | Zheng Shengtian, “The Avant-Garde Movement in Chinese Art Academies”, in catalogue of ‘I Don’t Want to Play with Cezanne’ and Other Works, Selection from the Chinese “New Wave” and “Avant-Garde” Art of the Eighties, Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, USA, p.19, 1991. |