Taking Paul Ricoeur’s discussion of the archive as a point of departure, Charles Merewether wrote, ‘The document functions … as a trace left by the past. Collected and organized, this body of material becomes the theoretical premise and material basis for the construction of the archive and the writing of history. From this perspective, therefore, traces are not remains and clues, but the material evidence, the stuff of history, the archive.’ i Since the inception of our project, Materials of the Future: Documenting Contemporary Chinese Art from 1980-1990, Asia Art Archive (AAA) has collected thousands of pieces of ‘material evidence’. This evidence includes over 70,000 scanned images, 75 interviews, over a hundred hours of video recordings, and hundreds of magazines, books, letters, photographs and other ephemera in the form of newspaper clippings, pamphlets and sketches. In order to introduce this material to as wide an audience as possible, we have developed a multipage website, to which this essay offers a preface, and a 50-minute documentary film called From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng: Cantonese Contemporary Art in the 1980s. This project has taken us over four years, and countless staff hours, and it would not have been possible without the trust and support of our loyal sponsors and a long list of collaborators, colleagues and friends, whose contributions are credited in the Acknowledgements section of this website.

Why an archive about Chinese art in the 1980s?

The reasons we embarked on this archiving project, with its indeterminate parameters and intangible goals, in addition to the ongoing responsibility of professional guardianship and preservation, may not be immediately apparent. Hasn’t contemporary Chinese art attracted enough attention? Hasn’t the history of Chinese art in the 1980s already been written? Is there anything more, of importance, to uncover? Indeed numerous books about the 1980s art scene in China have been published. As early as 1992, Lu Peng, with his colleague Yi Dan, published A History of Modern Art in China, 1979–1989 (Zhongguo xiandai yishushi, 1979–1989), which has remained a key reference book. In the same year, Gao Minglu, one of the most active art historians in the field, published A History of Contemporary Art in China, 1985–1986 (Zhongguo dangdai meishushi, 1985–1986)), which was followed by numerous articles and book chapters. More recently, Gao has published a two-volume compilation of source material about the ’85 New Wave movement. These volumes testify to the depth of his personal archive and his involvement in chronicling this important moment of intellectual exuberance and artistic flowering. The ’85 New Wave has also been the focus of two recent exhibitions and accompanying catalogues, organized by Fei Dawei at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing in 2007 and Huang Zhuan at OCAT in Shenzhen in 2007, respectively. These materials are primarily in Chinese.

English language materials about Chinese art in the 1980s also exist. An early observer was Joan Lebold Cohen who published The New Chinese Painting, 1949–1986 in 1987. More recently, Martina Köppel-Yang published Semiotic Warfare: A Semiotic Analysis of the Chinese Avant-Garde, 1979–1989, and AW Asia, under the editorial tutelage of Phil Tinari, has released two useful folders of material, with more to come. Exact titles and publication information appear at the end of this essay.

These publications form the foundation of a discourse. They are full of information and insight, but they are also highly focused, and to some extent, partisan. The authors of many of these valuable materials were not just historians: they were in large part energetic participants in the developing experimental art movement of the period. So while these accounts are closely observed, even historicized, they are necessarily incomplete. For example, the so-called ’85 New Wave movement, to take one of the most popular topics of inquiry, was an undoubtedly important phenomenon and from it emerged some of the most celebrated artists and critics of today. However, has the almost singular focus on this effervescent moment, which has become, in the minds of many, synonymous with the entire decade, obscured a more complex dynamic? Without diminishing the contribution of the pioneering artists and critics who participated in this event, how would a wider investigation of the circumstances within which the artists worked add meaning to their project? What other activities, exhibitions and events were taking place that would enrich our understanding of this transformative decade, its place in history and relation to the present?

Researchers looking for answers to these and other questions will want to return to primary sources, but access to these materials is extremely cumbersome. Institutional platforms supporting research and storage of contemporary Chinese art are limited. While there are individual initiatives in development, their plans for sustainable long-term support and public access are still unclear. The most durable institutions in China are still vested in the government sector, and while these museums, libraries and academies hold significant archives, their approach to collecting material about the 1980s has not been systematic or consistent, and their bias is often quite conservative. Primary research materials about art of the period, therefore, often remain in private hands, dispersed, scattered and vulnerable. People move, boxes get lost, and papers get thrown out. Even original works of art from the period are hard to find and images of this rare material are equally scarce and often of poor quality.

Reasons for the lack of institutional support for research about art from the 1980s are complex. Continuing sensitivity by the Chinese authorities about the political implications of the contemporary debate may be one factor. Another factor is economics. The recent market boom has focused resources on the opportunities of Now. The speed of change in China over the last 30 years has left little time for introspection, even less time to look back. The fragility of the infrastructure supporting research in the arts is, however, not unique to China. Many communities in Asia similarly suffer from the pressures of economic efficacy and the relentless sprawl of urban development that threaten to erase all traces of the past and relegate the responsibility for preserving cultural heritage to theme park developers and directors of big-budget feature films. Few art circles in any country have been able to resist the art market and media’s insistence on reducing contemporary art to a caricature and its history to a myth. Therefore, by focusing on the 1980s, this project not only responds to an urgent need to collect these increasingly ephemeral documents of change, but also attempts to create some distance from today’s spectacle to recover some of the historical complexity of the time in the hope of offering a richer context within which contemporary developments can be analyzed and understood.

About the 1980s

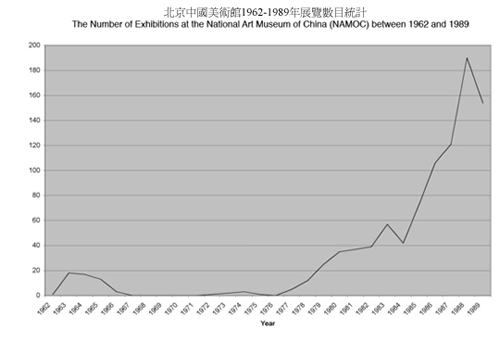

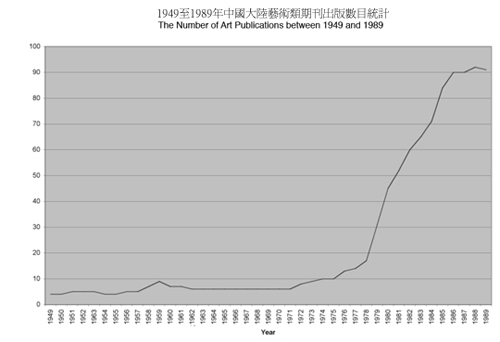

Suspended between the utopian politics of Mao Zedong and the pragmatic economic program of Deng Xiaoping, the 1980s was a pivotal decade. During the Mao period, roughly 1949 to his death in 1976, artists were controlled by the state on whose payroll they depended, and the value of their output was measured by its utility, namely, its ability to illustrate and support the objectives of the Communist Party leadership. In the 1980s, from an institutional perspective, most artists were still supported by the state but the objectives of the leadership were changing dramatically. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping made a series of watershed speeches at the 11th Communist Party Congress in which he called for the modernization of China. Urgent economic reform and increased foreign trade were at the top of his agenda. To achieve these goals, the central government established diplomatic relations with the United States on 1 January 1979 and embarked on a series of tentative but far-reaching experiments in private enterprise. The government began to decentralize agriculture and industry, establish special economic zones and introduce the market place as a platform for valuation and measure. Artists were encouraged to ‘modernize’ too, as were museums and publishing houses. Subsequently the economy, devastated by years of gross mismanagement during the Cultural Revolution, began to revive, and activity in the arts took off. The number of exhibitions soared and so did publications about art.

The 1980s was a period of expansion, but also instability. Continuing factionalism within the Communist Party leadership produced a political plot line that zigzagged between periods of great openness and conservative backlash. Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, both subsequently discredited, represented the liberal wing of the Party leadership. Under their indirect support, experiments in open debate and social freedom were attempted, and at times encouraged. The conservative opposition, however, remained intractable, succeeding in launching campaigns in 1983 and 1987 against spiritual pollution and bourgeois liberalism, code words for excessive Western influence and ‘decadent behaviour’. The last backlash of this decade culminated in the crackdown at Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989.

The unstable but rapidly expanding social space within which artists worked was fraught with great expectation and challenge. The limits of permissibility kept changing, and the threat of public censure was omnipresent, creating an atmosphere of tension but also of collective excitement. ‘Reading Fever’ was one example of the collective excitement that gripped the artistic community in the beginning of the 1980s. Barred for many years from information about China’s feudal past and the capitalist West, students became avid consumers of newly released publications, including translations of Western texts. These publications covered a wide range of topics, from Chinese antiquity and Chan Buddhism to existentialism, Freud and the history of modern Western art. Offering a language with which to articulate the contradictions embedded in their present predicament, artists became theoreticians and critics. They wrote clamorous manifestos, waged heated debates and experimented artistically in ways that were simultaneously insightful and self-absorbed, challenging and immature, idealistic and irresponsible.

AAA’s approach to the 1980s

In order to understand the impact of the 1980s, some historians have focused on political vicissitudes, others on economic reform. As archivists, however, our point of departure was the books and the written documents, both published and unpublished, which fuelled the intellectual debate of the period. Intellectual discourse was a hallmark of the 1980s, and it was as much about the search for self-awareness and social engagement as it was about the pursuit of pure knowledge. As Wang Du stated, ‘The Reading Fever of 1985 and 1986 served to form the individual values of artists and to elevate their character.’ ii ‘We were searching for explanations and answers,’ he continued, ‘and an ability to dialogue with society … to find ways to explicate our existence and to think independently.’ iii Hou Hanru has argued that the books published in the 1980s have had a long-lasting impact on Chinese society as well as on the art world, because these books ‘underpinned social values’ in addition to supplying technical information. iv

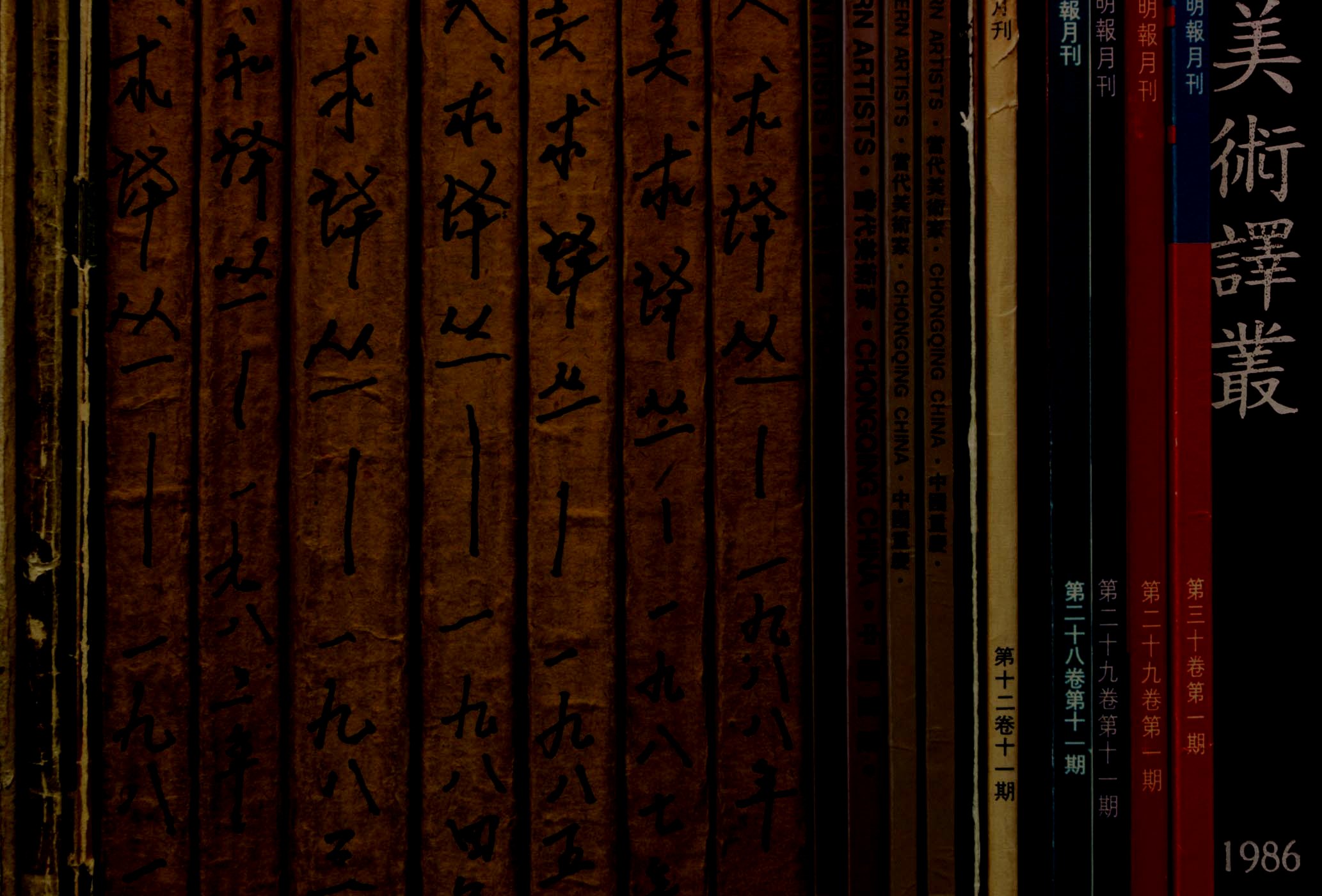

With the goal of developing a better understanding of the intellectual environment in which artists and critics worked, AAA conducted extensive interviews with active participants of the 1980s art scene—students, teachers and writers, as well as amateur and academically trained artists. We asked what texts they read, what writers they admired, what theories they studied, and what materials, both visual and literary, influenced their work. These questions invariably elicited a chain of memories about exhibitions, films, music, and of course, the people and incidents that contributed to their developing practice. Many influential books were translations from foreign languages; these were most often theoretical texts. Assembling an archive within this archive, we have collected many of the 1980s editions of these translated texts. We have also developed a comprehensive collection of contemporary magazines, journals and newspapers specializing in the arts, including those that were circulated for a limited period and discontinued by the end of the decade. These include a complete set of Fine Arts in China (Zhongguo meishubao), Art Trends (Meishu sichao), Art (Meishu), Jiangsu Pictorial (Jiangsu huakan) and others. It is on the pages of these publications that many of the debates were waged and influential works of art published, testifying to the heterogeneity of the period and its concerns.

The participants in this great wave of curiosity and debate were numerous and crossed generations, professions, geographic locations, organizational affiliation and position. The borders between the establishment and the so-called avant-garde were fluid. Champions of thoughtful experimentation included veteran artists, seasoned critics and teachers. These were joined by ambitious, young provocateurs. Names of some of these participants are well known—Wang Guangyi, Xu Bing and Huang Yongping. Others are less well known but equally influential—Zheng Shengtian, Shao Dazhen and Peng De. With a view to developing new insights and fresh material about the 1980s art scene, we have conducted videotaped interviews with a diverse range of participants, and have been honoured with the opportunity in some cases to collect, in other cases to catalogue and scan, their personal collections of documents and material. These personal collections hold a special place within our archive. For these we must specially thank Wu Shanzhuan, Mao Xuhui, Lu Peng, Zhang Xiaogang, Wang Du, Zheng Shengtian, Fei Dawei, Wang Youshen and Oscar Ho Hingkay.

Finally, based on a portion of the interviews and material collected during our project, we have produced the documentary film From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng: Cantonese Contemporary Art in the 1980s. Seeking to address a gap in existing histories, this film offers new information that will hopefully inspire further research and challenge our understanding of the contribution of artists from southern China. Loosely arranged as chapters of a book, this film purposely resists the structural coherence that relies on a single narrative or narrator. Rather its cohesion emerges from the links between disparate stories, as Bart deBeare would say, the ‘widely divergent lines that make up personal frames of reference’ to which the edited dialogue gives form. v Together these multiple stories suggest fresh perspectives, even tentative plot lines, from which alternative histories of contemporary art might be imagined and researched.

However compelling these stories and their alternative plot lines may be, as important are the questions that our evidence continues to raise. For example, given the sudden appearance and unequivocal impact of certain recurrent texts or series of texts in the 1980s, often about Western critical theory and art, what were the roles of translators and publishing houses? What was the basis of their editorial choice and how did this determine what people read and how they understood it? How influential were individual teachers and leaders in the cultural establishment whose support, even encouragement, may have balanced the admonishments that were intermittently issued? How do affiliations with certain academies and individual teachers create artistic lineages that impact the way art is taught and priorities are conveyed? What is the role of regionalism in the development of Chinese art? How did the economic reforms that accelerated after 1987 alter the terms of engagement within the Chinese society, between artists and in respect to their art project? What was the impact of tourism and the development of an incipient collector base made up of resident foreigners—diplomats, business people and occasionally students?

Further, that AAA is an archive of the region, and not just China, presents many opportunities. The depth of the China 1980s archive highlights the necessity of launching similarly targeted archiving projects in other Asian countries. It also suggests new possibilities for cross-regional dialogue and discourse to deepen investigations into issues of modernity in the region. Coming to mind are the efforts of cultural historian Winnie Won Yin Wong (MIT), who has sought to compare developments during the 1980s in Korea, China and Japan, and of Professor John Clark’s (University of Sydney) research into the parallel experiences and evolving art systems in Thailand and China in the 1980s and 1990s.

AAA acknowledges the politics of the archive: that in organizing we are exercising authority, that in selecting we are revealing a bias. Nonetheless, we hope that the traces of the past that we have preserved will inform the perspectives from which new narratives will be assembled and tested. Our goal is not to simplify nor sanctify; quite the contrary, it is to complicate and to question. Charles Merewether has called the archive ‘material evidence, the stuff of history’, but I am sure he would agree that history is plural and that parsing the evidence is about developing a better understanding of a past to which we are all connected, as much as it is about looking critically at the evidence that has been preserved in order to contest and even re-imagine the past about which we have been told. Along a similar vein, Qui Zhijie might consider our archive an archaeological site of the future and our collection drive an attempt to resist the forces of erasure. Referring to Foucault in the catalogue of a 2005 exhibition of emerging artists, Qiu writes that ‘Archaeology is an attitude’ and calls upon his fellow critics and artists ‘to ceaselessly excavate the traces of that which has been erased, intentionally or unintentionally through the writing of history, in order to approach the truth.’ vi While truth may be an elusive, if not impossible, aim, its pursuit implies a process of ongoing excavation, interrogation and reinterpretation. Accordingly, this project seeks to inhabit the gaps in our incomplete histories and to expose the silence and caesura within the historical record’, as Merewether would propose, and to explore the interpretive possibilities of new evidence. vii Further, like Bart deBaere, we also believe that the archive is about potentiality and the ‘stream of possible narratives; from storage and access to stories, to connections and palaver’ that give rise to the contingencies embedded in our cultural history. viii Therefore, whilst phase one of this 1980s archiving project is complete, AAA will continue to collect, document and preserve the ‘stories, connections, and palaver’ as well as the ‘widely divergent lines that make up personal frames of reference’, and we enjoin our friends and colleagues to do the same. For we believe that in this material we will uncover the evidence that not only links our present to our past, but offers us the opportunity to continuously re-imagine our future.

| Notes | |

| i. | Charles Merewether, ed., ‘The Language to Come’, The Archive: Documents of Contemporary Art (London: Whitechapel and MIT Press, 2006), 121. |

| ii. | Jane DeBevoise et al., From Jean-Paul Sartre to Teresa Teng: Cantonese Contemporary Art in the 1980s (Asia Art Archive Hong Kong, 2009), interview with Wang Du [DVD]. |

| iii. | Ibid. |

| iv. | Ibid., interview with Hou Hanru. |

| v. | Bart deBaere, ‘Potentiality and Public Space’, InterArchive (Koln: Verlage der Buchhandlug Walther Konig, 2002), 107. |

| vi. | Qiu Zhijie, Zuo Jing and Zhu Tong, Archaeology of the Future: The Second Triennial of Chinese Art (Hubei: Hubei Fine Arts Publishing House, 2005), unpaginated. |

| vii. | Merewether, ‘The Language to Come’, 175. |

| viii. | deBaere, ‘Potentiality and Public Space’, 106–07. |

| Selected Bibliography |

| Cohen, Joan Lebold. The New Chinese Painting, 1949–1986. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987. [English] REF.COJ |

| Fei Dawei, ed. ’85 New Wave: The Birth of Chinese Contemporary Art. Shanghai: Century Publishing Group, 2007. [Simplified Chinese] EXL.CHN.ENW |

| Gao Minglu. A History of Contemporary Art in China, 1985–1986. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1991. [Simplified Chinese] |

| _____ et al. The ’85 Movement: The Enlightenment of Chinese Avant-Garde. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2008. [Simplified Chinese] REF.GML |

| _____, ed. The ’85 Movement: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2008. [Simplified Chinese] REF.GML |

| Huang Zhuan, ed. Creating History: Commemorative Exhibition of Chinese Twentieth-Century Modern Art from the 1980s. Guangzhou: Lingnan Art Publishing House, 2006. |

| Köppel-Yang, Martina. Semiotic Warfare: A Semiotic Analysis of the Chinese Avant-Garde, 1979–1989. Hong Kong: Timezone 8, 2003. [English] REF.YKM |

| Lu Peng and Yi Dan. A History of Modern Art in China, 1979–1989. Changsha: Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 1992. [Simplified Chinese] REF.LUP |

| Tinari, Philip, ed. U-TURN: 30 Years of Contemporary Art in China, nos. 1 and 2. New York: AW Asia, 2007 and 2008. [English] PER.UTU |